D E F T C U T S _

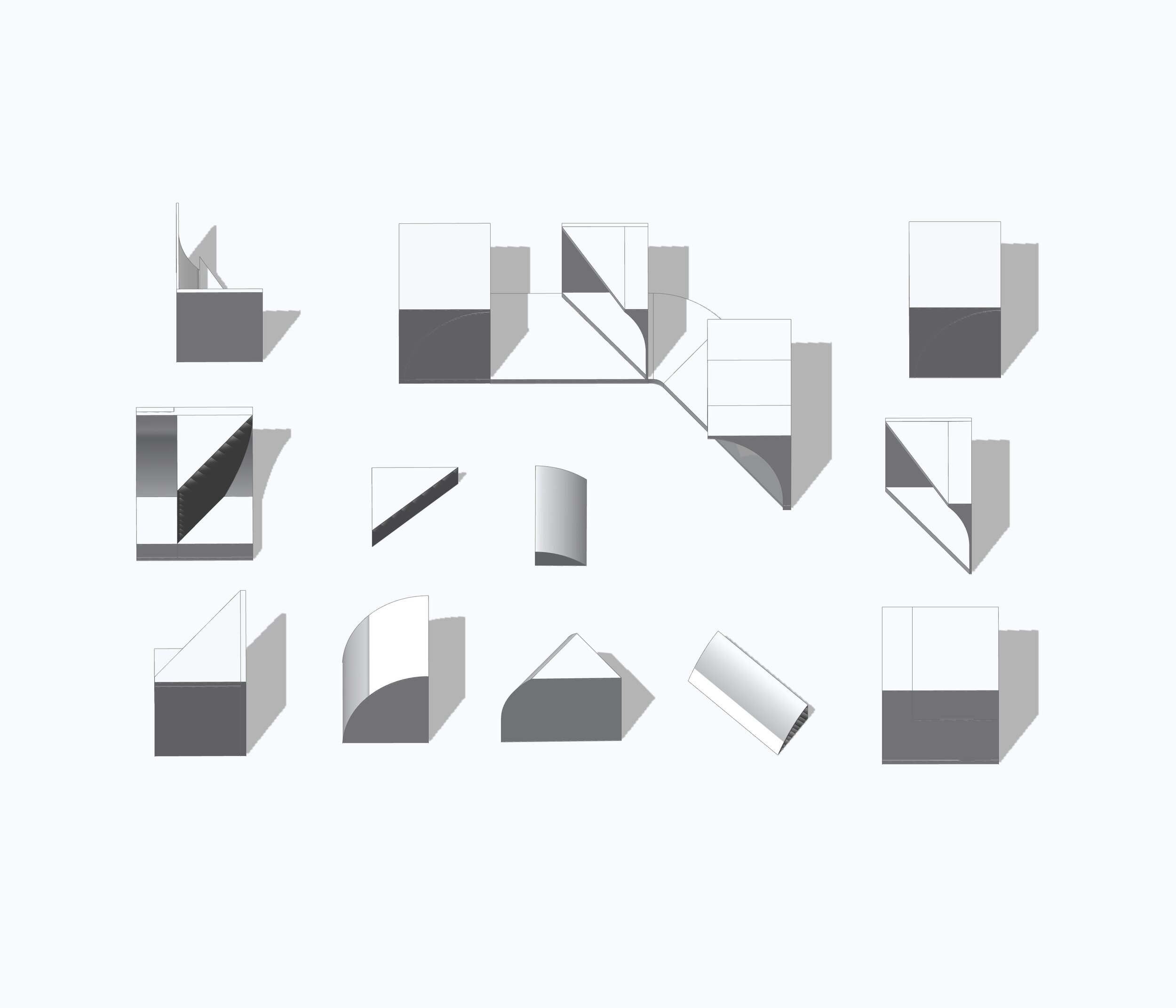

V I E W I N G P O D S _ The exhibit structure consists of 9 total ‘pods’, 6 voided, that are attached by a flat floor or ceiling element, and 3 floating solids. The orientation of the design counters a traditional gallery box by offering oblique view angles of the work and non-frontal approaches; a wondering discovery of the works hidden around bends and niches. The design is flexible up to 40 student projects or less, by choosing which walls receive the 2x8 branding after student submissions are completed. Painted white or left as natural birch plywood allows either projects or graphics to be displayed.

The exhibit structure consists of 9 total ‘pods’, 6 voided, that are attached by a flat floor or ceiling element, and 3 floating solids. The orientation of the design counters a traditional gallery box by offering oblique view angles of the work and non-frontal approaches; a wondering discovery of the works hidden around bends and niches. The design is flexible up to 40 student projects or less, by choosing which walls receive the 2x8 branding after student submissions are completed. Painted white or left as natural birch plywood allows either projects or graphics to be displayed.

S H A D O W + S I L H O U E T T E _ Flattened projections receding from everyday acknowledgment as shaded effects of physical objects casting outlines. Does not adhere to original form. Changes shape and meaning as viewed from various angles or as multiples come together to form new wholes. Abstraction of these intangible concepts are seen through the everyday banal towards figural opportunities. Shadow is texture or image and silhouette forms outlines. Silhouette is figure in pure contrasting shadow lit from behind. One must rationalize a three dimensional object through internal perspective of abstraction. Silhouette requires a view through two dimensional shape; depth of space collapsed, and graphic edges pronounced. Meaning is subjective.

A E S T H E T I C S T R A T E G I E S O F T H E F O R M I D A B L E _

For better or worse, military development is largely responsible for some of mankind’s greatest technological achievements. While instruments of warfare are commonly associated with power, destruction, death and intimidation, often these militarized objects can elicit an aesthetic response. Lockheed Martin’s F-35 Lightning II is a highly engineered combat aircraft designed to perform complex ground attacks and defense missions for the United States Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy. Although the engineering of this machine is paramount to its performance, one might begin to speculate whether there is aesthetic intent in something so visually striking. Perhaps the best way to answer this question would be to consider modes of architectural analysis and thought to a new domain in order to reveal its aesthetic strategies.

An Act of Close Reading

The project of close reading is one that assumes there is content. It is to take something that has a seemingly clear conclusion and to unravel it and make visible its complexities. The only reason to perform a close reading of a militarized object like the F-35 is to make the claim that these are not just efficiently engineered objects. Instead, these are inherently aesthetic objects operating within a culture that surrenders attention to them. But like all acts of close reading, what was once so clear is all the sudden unclear. One might assume that any attempt to extract an aesthetic strategy would be rather straightforward; let’s build the fastest and highest performing war machine possible and call it a day. It’s a fighter jet, not a beauty pageant. Instead, through this act of close reading, the object reveals itself as an embodiment of the complexities of society and culture in general.

In 1996 the largest acquisition program in the history of the Department of Defense (DoD) was announced and the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program began. The JSF was created to replace numerous aircraft as well as develop a common fighter that would succeed existing types. The U.S. military desired a low-cost multi- role fighter to serve the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. A secret competition between Lockheed Martin and Boeing began when the two companies were awarded a four-year design development contract. Both would produce a ‘concept demonstration aircraft’ capable of exceptional combat prowess, carrier-approach handling, and short takeoff - vertical landing (STOVL) capabilities. This meant the plane would need to shift to and from hovering in mid-flight. Ultimately, the winner would receive a $200 billion defense contract to develop what could potentially be the last manned jet fighter for the U.S. Military and its allies. Technological objects like the F-35 have profound effects on how we perceive a nation and how its prestige is expressed and communicated via its war apparatus. Here we will identify and isolate an aesthetic strategy operating through our engineered modalities.

[Fig.1] Two F-22A Raptor in column flight. [U.S. Air Force photo by TSgt Ben Bloker]

The Strategy of Casual Adaptation

At the time of the competition, the current gold standard of American fighters was the F-22 Raptor, also designed by Lockheed Martin. [Fig.1] It was expensive, and not the all in one fighter the JSF required. The Raptor provided a wealth of proven design ideas including its radical new shape which was optimized primarily for stealth. The F-22 Raptor’s geometry is designed to give it an extremely low profile, making it nearly invisible to oncoming aircraft using high-frequency fighter aircraft radar. The basic principle of stealth technology is to make an airplane invisible to the enemy. For this to work effectively, an aircraft’s shape needs to deflect incoming radio waves away from the enemy radar rather than towards it. To further obscure the warplane’s visibility, an aircraft is covered in materials that absorb radar signals. This reduces its visibility on a radar screen. In the development of the F-35, Lockheed Martin decided not to completely redesign the plane, but to build on the previous stealthy shell of its successful F-22 in what can only be considered an act of wartime Casual Adaptation.

[Fig.2] F-35A Lightning II aircraft. This image is a work of a U.S. military or Department of Defense employee, taken or made as part of that person's official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain in the United States.

Experimental composers in the 1940’s began exploring techniques that involved using recorded sounds as raw material. This particular style of composition came to be known as Musique Concrète. It was an attempt to create new forms of classical composition by utilizing and reinterpreting familiar sounds to create an original work. Decades later, this technique is now referred to as sampling and has since been adopted by several musical genres. When the idea of sampling permeated throughout popular culture, its legitimacy as a creative output came into question. But if one sets this question of authenticity aside, we can instead prioritize its ability to warp the familiar. One might argue that Lockheed took a rather conservative approach in designing the F-35. Instead of starting entirely from scratch, Lockheed used the F-22 as raw material. Its performance capability in air to air combat relies on its aerodynamic shape that is as visually striking as its capabilities. The strategy became one of Casual Adaptation; to modify a series of cross-sectional profiles that would accommodate the hardware needed to meet specific performance criteria.

In its mediated and classified state, the F-35 is only knowable through its name, its photographs, and the limited documentation offered to us by its creators. In the early twentieth century, Sigmund Freud wrote about the physiological concept of the uncanny. The uncanny breaks up any comfort of knowing what is immediately familiar leaving us justifiably flustered. Upon close reading, the F-35 is nothing more than a sampled version of its ancestor. It is both old and new; cautiously occupying the territory of the uncanny. What is useful to us is considering the territory the plane occupies and speculating on how we can embed similar aesthetic strategies to our design processes in hopes to produce a similar reaction. Through close reading we able to examine the gap between the familiar and the uncanny and arrive at a serviceable methodology. In this case, the strategy of Casual Adaptation.

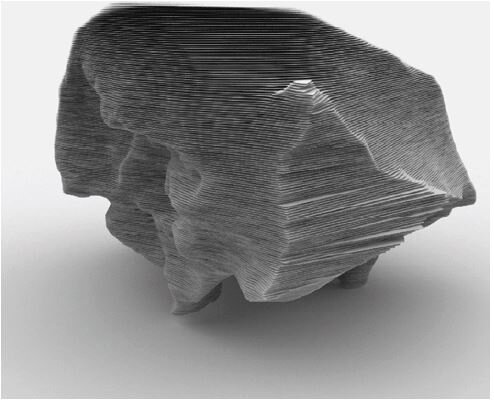

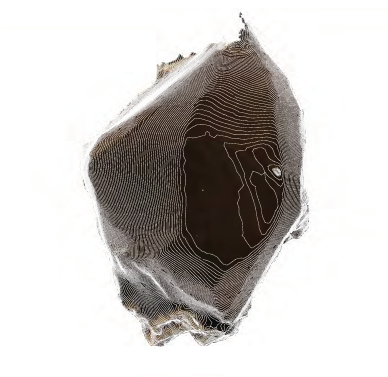

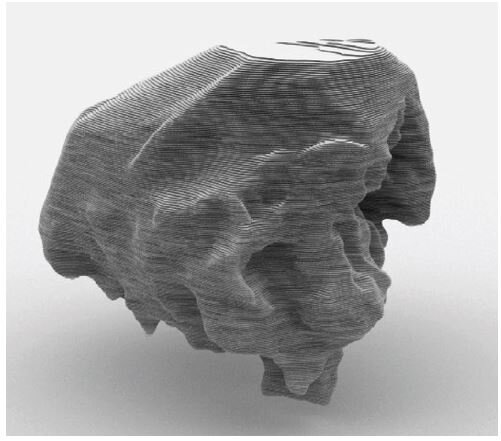

P O S T - S C I E N T I F I C G E O L O G I C A L F O R M S T U D I E S _ Throughout history, science has tried to better understand our world by attempting to logically explain nature. The geological object is often viewed as something that can be fully grasped and understood by various scientific means and methods. Our proposal for a “Post-Scientific Museum of Geology” aims to confront this traditional approach, by attempting to create a provocative experience that becomes a medium for a new understanding of what nature is to us. The idea is to explore various properties and characteristics of a given stone. The final form was derived from in depth studies of various geological structures embedded within this particular stone. Advanced digital techniques of drawing, scanning, modeling and fabrication were utilized to generate the overall form and spatial sequences within the building.

T E C H N O - A E S T H E T I C S _ Techno Aesthetics includes both places of power and places of high technology. Unlike high tech architecture, structural expressionism or machine architecture, this term does not describe an architectural style, but rather imagery of increasingly more influential fringe typologies. This categorization of spaces are typically devoted to protecting a single highly technological concrete object, as in the ULA launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base or serve as an apparatus for extensive operations, as in the VLA Radio Astronomy Observatory. Data, information and electricity are abstract, but become a source of aesthesis when mediated by an adequate instrument that enables human perception. The complexity of the mediator allows partial access to an intangible commodity as part of the overall aesthetics of technology. We can not fully access the technology itself, it can only be understood through quantitative means and the physical materiality of the apparatus. The aesthetics of technology requires specific reasoning. To the visitor, it must be highly technological because it appears that way, or for users and especially the designers of the space, it must look highly technological first and therefore it will be.

Tours of JPL give access to only a few rooms, including the highly published “big white room” where JPL employees are dressed in white bunny suits. This room is a mix of Ascetic and Schizo Tech aesthetics, a spotless white room with scattered Mars Rover objects and very low tech objects. Arrays of technological objects present an aesthetics of much more far reaching power than a closed space. Understanding the functionality of the objects produces an even more dynamic sensibility to their existence. This set of radio satellites has an intense semantic power. Unlike the true associations in the arrays of identical solar energy capturing mirrors in the desert, the LHC at Cern operates through compatible associations of the individual pieces. Each strand weaving perfectly through all the others. The LHC has a Technicolor Science Aesthetic, displaying many bright colors. The Techno-Aesthetics of these “places of power” require a simultaneous absorption of the materiality, scale and complexity of the physical objects they are designed for. The technical functionalities reach beyond the locations of the buildings themselves to include military, space exploration, energy and communications.

Much like the aesthetics of material technologies, mechanical technologies rely on materiality and the physical presence of the technology itself. What you see when looking at a mechanical technology is the actual machine, the parts moving or a casing that houses the parts inside. You can physically witness the technology of the thing taking place. What we would consider today as an advanced technological space, where advanced scientific research takes place, differs greatly from that of a mechanical space and of a machine aesthetic. The technological complexity of objects we see in a NASA laboratory, a nuclear power plant or a 500 meter aperture spherical telescope is only the material portion of the entire technological apparatus that allows us to produce the more abstract intangible technology of radio waves, energy or communication with a Mars Rover.

![Isometrics [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994922642-SU48TECUB2IOW3WA4WM7/Isometrics+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![Isometrics [Converted]-04.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994937468-68XT3P70A0059OHAFAJZ/Isometrics+%5BConverted%5D-04.jpg)

![Isometrics [Converted]-03.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994936603-59WX9XC8VBMQTMNXGSL3/Isometrics+%5BConverted%5D-03.jpg)

![Isometrics [Converted]-02.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994924113-88DQV513DR2I6NCEA12L/Isometrics+%5BConverted%5D-02.jpg)

![Elevations [Converted]-01.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994906401-UH6C7F1RL2SFMRCZM70P/Elevations+%5BConverted%5D-01.jpg)

![Elevations [Converted]-02.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994907827-HJY17LAITMQJ81YN4GOQ/Elevations+%5BConverted%5D-02.jpg)

![Elevations [Converted]-03.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994912738-U7P5HMX11VPGXVNN8PB9/Elevations+%5BConverted%5D-03.jpg)

![Elevations [Converted]-04.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603994913250-UCUPGW656ZKX2SUNOYAT/Elevations+%5BConverted%5D-04.jpg)

![[Fig.1] Two F-22A Raptor in column flight. [U.S. Air Force photo by TSgt Ben Bloker]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603988649882-NL9ZWW9EHXCWRU3DMEW0/750px-Two_F-22A_Raptor_in_column_flight_-_%28Noise_reduced%29.jpg)

![[Fig.2] F-35A Lightning II aircraft. This image is a work of a U.S. military or Department of Defense employee, taken or made as part of that person's official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain in th…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5301bafee4b0f0275ec58243/1603988782045-VKNLZZ3DCF8TCWBXEP18/800px-thumbnail.jpg)